Fan Court School

Cazalet, Class of 1947

John Wilkinson

Alongside photographs, John shares his memories of Fan Court School, the Second World War and his account of the school's foundation:

John Wilkinson attended Fan Court School between 1942 – 1947 before progressing to Harrow School. He later completed his undergraduate degree at Oxford University. From 1957-1966 John worked for oil companies in the Middle East and Laos before returning to Oxford to complete his DPhil, where he was also awarded a D.Litt, the highest Doctorate Oxford University can award. In 1969 John began teaching at the University and remained there until his retirement in 1997. John is an Emeritus Fellow of St. Hugh’s College, Oxford and is regarded as a leading expert on Oman.

“Its origins are interesting. The initial driving force came from two masters, G H I Snape and Geith (sic) Plimmer at a prep school (St Michael’s, Uckfield) that was favourably inclined to CS but not prepared to go the whole hog. Guy Snape had been at Harrow, where he contracted polio, hence the limp and need to walk with a stick; he then read History at Hertford College Oxford. He was a lovely, kindly man, though he had his favourites and, let us admit it, was a bit of a snob. He lived in a little room in the main part of the school and was the person the boys saw from the rude awakening when we all lined up to dash under a cold shower (during which he often gave us the war news), as also during our free time when he generally leaned propped against the radiator in the main hall, and finally making sure we had all gone to bed. I eventually won his approval, and with it invitations to listen to concerts on his wireless, including the first performance of Vaughan William’s Antarctic Symphony. He also brought history alive and I still have my little notebook illustrated with cuttings and my own efforts. Mr Plimmer, a New Zealander in origin, resigned shortly after the school started but was a driving force behind the scenes and Chairman of Governors under its new constitution drawn up after the war started. Another master, formerly at the Uckfield school, F(rancis) G. Williams joined them in February 1932. He left for the war in 1941 but returned in 1944 and took charge, inter alia, of the sports side, football and cricket (rugger was introduced the year after I left); the small boys mostly played rounders. Plimmer was replaced by A.G. Lole, who came from a very different background. Although also ex-Oxford (Lincoln), he’d seen service during the war and subsequently worked as a mining engineer above and below ground in collieries, many of which were now in deep trouble. Attracted by the CS atmosphere he accepted the post and like the others gave of his all, teaching maths and carpentry: he and his wife lived in Virginia Water. Though kindly, he was not one to try the “CJU (Coo, Jolly Unfair) Sir!” approach on. I was a bit miffed however, that when I solved the maths problem which he said no one ever got right, I did not receive any congratulations. My proud return on holidays with a little book stand from his carpentry class, with ends duly tenon and morticed, enthused my father to the point of starting to build a tool collection for me. He must have been sorely disappointed when his son evinced little aptitude at engineering matters (though not entirely).

However, to return to Fan Court’s beginnings. The first attempt was small scale in

temporary housing at the Lodge at Banstead in Autumn 1932, but during the following year the constituting body decided to found a first-class preparatory school, essentially for public school entry up to scholarship standard based on CS, but not a “Christian Science School”. While in search of a suitable location the school, having outgrown Banstead, moved into a larger property, Warren House in Stanmore which Sir John and Lady Mildred Fitzgerald had generously put at its disposition. To achieve greater support and impetus however, they clearly needed a Headmaster with wide experience. T(homas). C. Elliott (1892-1969) came from a Quaker family and attended the Society of Friends school at Sidcot in Somerset. After reading French at Manchester University he continued with a Licence-en-Lettres from Paris. He subsequently became a housemaster at Leighton Park, also a Quaker School, before returning to Sidcot as Headmaster in 1930. He met his wife (née Janet Mary Payne 1902-1991) who had read English at Girton (Cambridge) at a teachers’ conference, and they married early in August 1929. A couple or so years later they converted to CS, and he had no alternative but to resign from Sidcot, to that school’s great regret. “Not knowing whither they went” in the Great Depression with two small children, John and Gillian (August 1931-July 1986 she was the only girl in the school). Trelly (as he was affectionately known between the boys) was just what the new Board was looking for and he accepted its offer (wef 1 January 1934) with no renumeration other than board and lodging. For long the governors wrongly presumed that the Elliotts had private means and when they did finally fix a salary it was at half what he had been getting at Sidcot. On her side, Mrs Elliott was prepared to run the housekeeping and catering, as well as taking charge of the well-being of the boys for free. This she did admirably giving the little ones a real home from home feel, and she was also successful in keeping on good terms with the medical authorities. GHIS generously stepped down and accepted becoming Second Master, like all the others, at a pittance.

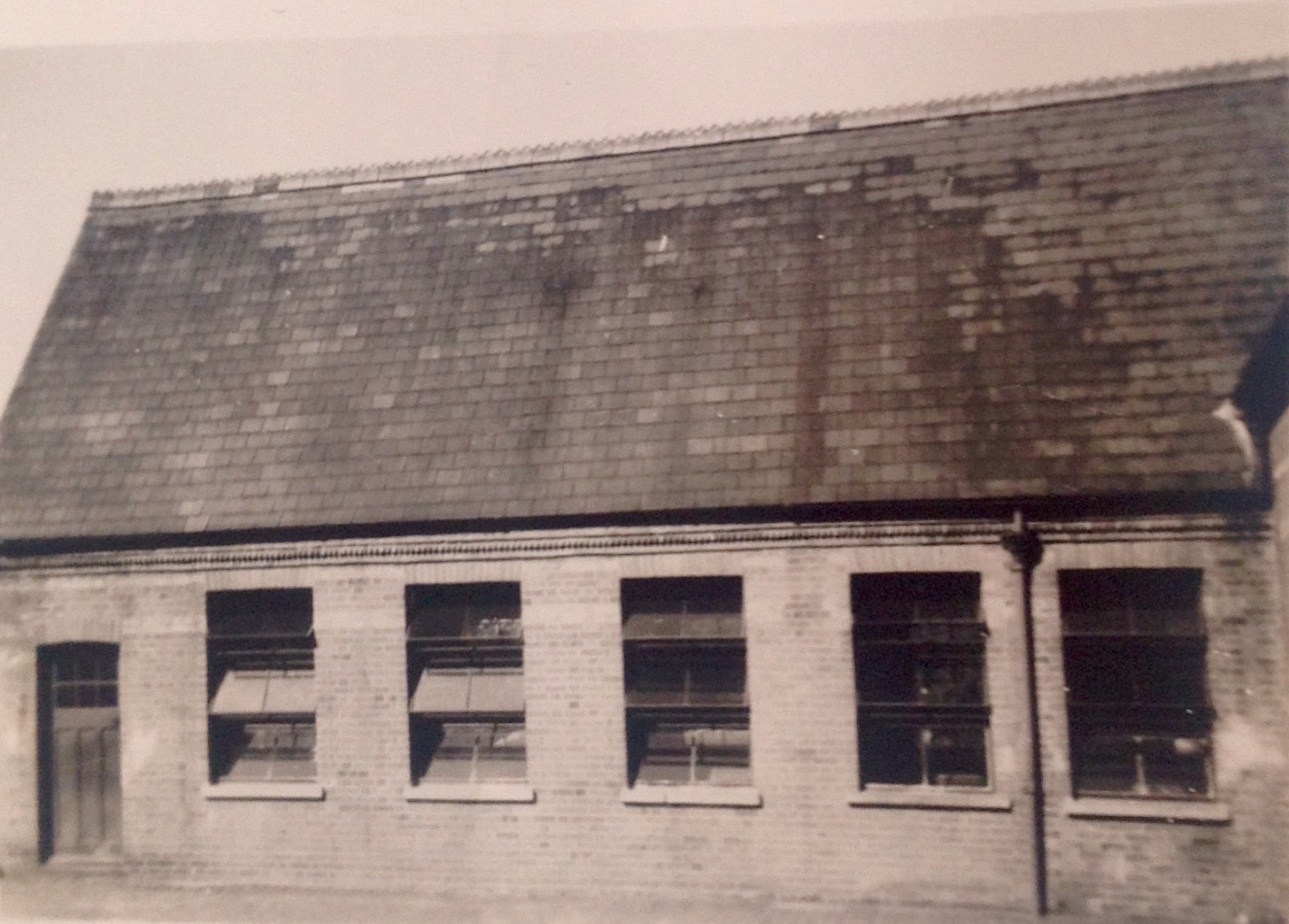

The school was now given a formal constitution (a charitable organization unlike most prep schools) and raised sufficient funds to acquire the Fan Court property at Longcross (near Chertsey) with 30 acres, part of the estate of Sir Edward Stern, a former High Sherriff of Surrey. Originally built between 1818 and 1820, the main house was largely rebuilt by the architect William Tarn later in the century. With its servants’ quarters and the old large stable block on higher ground beyond, it showed considerable potential for conversion into a school. A further 27 acres of land suitable for playing fields were acquired through the generous loan of Capt. Cazalet (member of an influential family, MP for Chippenham and a strong proponent of Zionism) .

It was a very bucolic setting. The house stood above two terraced lawns in its main aspect, around which lay a line of big trees and a bordering promenade. Tree climbing was allowed, including the big Wellingtonia (no “elf and safety” then). Beyond was an uncultivated field at the bottom of which was a natural pond and the shrubbery bordering the main drive. This wound its way from the main Longcross entry through the estate to the higher ground where it joined the back road to Lyne. On the other side of this road during the war was an ammunition dump, of which more anon. The rhododendron shrubberies were extensive and along with the azaleas produced a colourful setting: we were free to wander in most places except the lawn in front of the Elliotts. The pond was full of fascinating things for little boys, pond-skaters, frogs’ eggs etc, and we were allowed to have our own collections in a variety of glass containers of tadpoles and the like in the conservatory. The grass snake from the field however, I think was banned. It was all part of the general encouragement for observing and respecting nature. Collecting birds’ eggs was right out, though for the few enthusiasts (notably Ibbotson), not butterflies, but finding and watching nests was encouraged, even though occasional over-enthusiasm for looking into the proximate nests of the less wary birds did occasionally lead to desertion. I vividly remember the thrill of discovering the little ball-like nest of a pair of long-tailed tits in one of the Rose Garden shrubs. Participating in estate work once a week was also part of the agenda, a very vital contribution during the war when collecting twigs and branches was essential for literally keeping the home fires burning.”

“Just how extraordinary the Elliotts were only became clear when reading what I could find of the school’s history, particularly so during the war. There was no question of Trelly’s authority, but his patience was unbelievable, and he worked on the principle that his charges should be kept occupied, happy, and calm (my father’s efforts to make me sit still and silent for a whole minute were much less effective). At mealtimes there was a moment of hush before his little bell tinkled and general hubbub ensued. And silence once more reigned at the end of the meal. When I arrived, I was cheeky, though to some extent unwittingly, perhaps because I had been spoilt and still inclined to tantrums like many small boys. I was put on the Elliotts’ table and learnt to behave and talk politely. Sending the unruly to run two “rounds” of the bordering promenade surrounding the main garden area was his standard technique of dealing with the over-excited. And I remember when I threw a stone (like many little boys) and accidently broke a small window at the back of the house he simply called on the culprit to own up at assembly. On the second time there was no threat of a group punishment. He simply reiterated his demand and I confessed and was docked the cost. There was no corporal punishment. I once received one wallop with a slipper when the dormitory monitor ordered me to report to him for disturbing the peace, and the whole school, or that part of it involved, similarly received a single wallop each when we broke out at night to sit on the lawn around the end of the war. The first time had gone undetected, but on the second occasion we were met by him as we crept back in. And despite the drawing room being under the Elliotts’ quarters, they never complained when I used to practice on the grand-piano there and try and thump out the Rachmaninov No 2, the score of which our visiting music teacher, Miss Bowyer/Mrs Katz, somewhat unwisely lent me. And he taught us French. I still remember when he came one evening to congratulate me on some composition I had done (Une promenade dans la forêt). In addition, he was active with the chain saw on the estate and we would regularly see him carrying the swill to the pig sty. But that was the what we boys saw.

He and GHIS (Snape) have recorded some of the problems and indeed opposition to getting the school started in a booklet Fan Court 1932-68 . When TCE took charge, there were 17 boys and by summer term 1934 construction progress was sufficient to permit the move to Fan Court proper. The academic year 1935-6 started with 47 and the classroom block in the old stables, as designed by TCE, completed. Shortly after, a gymnasium was added with the help of all, including boys who raised money during the holidays; and it also served as an assembly hall for Parents’ Day (I made my first public performance playing the little Mozart C major sonata on such an occasion!) That was the layout I knew during my time. The main classrooms were located on the upper courtyard and from the belfry, frequented by bats, steps led down to the lower yard, with the adjoining gym on the right and Mr Lole’s carpentry-workshop on the left, where at break we played “Kick the can in the Courtyard” or tag. At the bottom of the steps was the art room, where, the mother of one of the boys, Paul Sexton, took classes (she once asked us to paint an exotic bird, and I finally had to admit that I did not know what exotic meant).

1935 saw the arrival of Mary Burt (>Willcox 1944), who had a diploma in Education from the Froebel Institute, and basically took over the junior school. One of her tasks was to supervise and correct our Sunday letters home. We didn’t seem to think this an intrusion on privacy: in any case mine at least were mostly on the line “Yesterday we had films. They were…” . She also had two brothers, comedians, “the Burt Twins”, who used to come and entertain us on occasion. Her husband, Ray J Willcox, a Methodist, arrived about the same time as me, thus completing the main body of teaching staff of my period, though there were some temporaries who came and went. In the course of the remaining pre-war years a bursary fund was started, and the number of boys sufficient to add a fourth house, Cazalet (mine). Houses, were in fact simply administrative units and we lined up in a ground floor room between the conservatory and entrance hall (with its small billiards/snooker table) where we also had our own lockers. There was no real competition between the houses and sport in fact was low key, with the aim of bringing out the best by sportsmanship rather than competition. In any case there were no games against other schools during the war and its aftermath.

By the end of the year 1938-9 the school was full, the fees raised to £60 per term, an increase of pay finally accorded the staff, and the budget beginning to come into balance. A new funding campaign was now envisaged to make the school economically viable, and to pay off its debts.”

“The war years: evacuation. The outbreak of war resulted in a fall of pupils to 42 and the school’s financial survival imperilled. Serious consideration was given in June 1940 for evacuating to Canada or the Bahamas. My father, a railway construction engineer, who had re-joined the army in 1937 after having served since 1914 throughout WWI was now responsible for planning and maintaining army camps and barracks in the Bournemouth-Poole region. He knew perfectly well that Poole harbour where we lived was one of two areas that Hitler’s seemingly inevitable Operation Sea Lion would land after the famous Churchill speech and Goering had mastered the air. So there was some talk of sending me out to South Africa with the lady who ran my nursery school, but Thank God not: I would have never seen my parents again until after the war. Instead, in May he sent me with my mother to a small hotel in Newby Bridge run by CS friends, and like most other FC parents decided to soldier on. After our return following the Battle of Britain, he put me in boarding school at Crichel House, to which Dumpton had been evacuated, for the winter and spring terms (1945-6) and it was there that I first learnt to play Rugger. The regime was not cruel but the winter cold was dreadful and fear of the cane basically maintained discipline, as in most prep schools of that time. I can still remember the effect on the boys of the news, “Nicholson’s being caned”.

Fan Court: the early war years. After the decision to soldier on at Fan Court, the numbers picked up and the first inspection by the Board of Education in 1941 reported very favourably on the Elliotts, the devotion of the staff, the politeness and friendliness of the boys and their keenness on their work. And despite the insufficiency of Latin (Greek was not taught) and the need of more attention to English Literature and Nature Study (perhaps the conservatory conversion was the result?), the school was winning scholarships to some of the major public schools. By 1940 it had old boys in all of the services, four of whom failed to return. That must have given the former Quaker food for thought.

But the strain of keeping the whole thing running in the face of financial constraints, rationing, lack of domestic staff, the black-out and fire-watching, new responsibilities for masters in the Home Guard (TCE was air-raid warden for the whole area), the departure of some on service, along with the responsibility for our safety was not really appreciated by their charges. The night raid in February 1944 when a bomb hit the ammunition dump and blew out all the windows on the south and east side of the house, where TCE picked a small boy out of his bed under a large plate glass window with its expanded steel screen lying atop, leaves absolutely no memory with me. Perhaps because I was sleeping on the other side, or the fact that no one was hurt may have blanked my mind. It may be that “the courage of the boys at that time was wonderful”, but I suspect that it was more likely that we got a vicarious thrill out of such events.

Apparently, all was repaired by June, but because of the “jet-propelled bombs” as the school magazine described them, we were sleeping in the make-shift dormitory in the old stable block basement, “The Ark”. Of the doodlebugs (V1s; we were immune from V2s) on the other hand, I have the most vivid memory. My first “encounter” with a flying bomb was in the Rose Garden when I heard one passing in the cloud. As instructed, I lay down and it cut out, fortunately drifting before falling far away. The second was a very different affair. As per usual I suppose, I was last leaving The Ark and crossed the courtyard on my own when a doodlebug flew straight overhead in a clear sky under full propulsion. I simply stood and gawped: I can still see it today. On the other hand, the privations of food rationing passed us by: basically, we knew no other. Some of us went out riding at a place the other side of a military training area where we could pick up all sorts of exciting bits and bobs of butterfly bombs and the like en route: when we got back too late for tea, we happily feasted on mustard, salt, and pepper spread on bread. The small butter ration was kept for essentials. So when in the San in quarantine for one of the usual childish ailments and consequently missing the end of term feast, a tray was sent up to me with a small pat of butter, I simply swallowed it whole and nearly brought up.

Relations between the pupils at Fan Court was pretty relaxed; there was no real hierarchy, we generally addressed each other by surname, and I was unaware of any serious bullying, or physical fighting. But boys of any ilk are not angels and can be nasty, sometimes unwittingly and teasing could get to the point of cruelty. One poor boy (Irons) who suffered from eczema was mercilessly imitated for his scratching. And there was another boy who liked to stir it and build up a following: in my case by accusing me of making the great-tits in the may tree desert. There were also the dares like pouring water down wasps’ nests. More serious was the ammunition dump. We were allowed to make fires and roast chestnuts in the upper field, but the temptation for some to break into the ammo dump on the other side of the road and explode bullets in the fire was too great.

I more or less steered clear of serious trouble and had my own set of friends, particularly Robin G, Bobby W-S, Billy R whom I sometimes visited at Brockenhurst in the holidays (his father Commander Reid, I think became a governor), Robin A, and Hendy-Clee (John H-C). But I’ve since recognized that there was a latent sense of adventure in me that first found expression during National Service, then in organizing and leading a University Expedition to Kurdistan in 1956 when at Oxford, and finally found fruition when I took up Alpinism in a big way after having worked in the Middle East and Laos in the oil business. Climbing with friends from very different backgrounds finally knocked any latent snobbishness out of my system . While sport was not a high priority at the school, there was a game we occasionally played, far too occasionally for me, called flag raiding. Two teams occupied the ground on either side of the drive (neutral ground) and the aim was to defend ones own flags and grab those of the enemy’s base (respectively the apple store and the woodshed). Crawling through the shrubbery, observing, and using wiles to outwit the opposition gave me a thrill that soccer and cricket never did.

Our regular weekday evening entertainment was Dick Barton, Special Agent, in which we crowded around the wireless in the library (which also served as assembly room in the morning). No women intruded on Dick, Jock and Snowy’s derring-do, any more than they did on our preferred reading, the Biggles books. (At home ITMA was compulsory listening on a Thursday). On Saturday some entertainment was provided, usually films, while after Sunday School, visiting parents were allowed to take their offspring and friends out to lunch (back by 6pm): and in the evening we were read to, normally by then, RJW. Fire over England; The Lost World, and much less amusing the interminable Captain Hornblower – “Man the main top mizzen mast”, whatever that was! RJW was an avid philatelist, as was I, and approval books circulated (British Empire stuff, of course). He and his wife lived in the flat above the garages in the Upper Courtyard and occasionally I was privileged to see his collection.

Other scattered memories are of the Lysanders and other biplanes in the training school not far from the top of the playing fields. Of the foil intended to confuse the radar of enemy planes which we found scattered around the grounds [this was “Window”, first used to good effect in operation Gomorrah for the devastating firebombing raids on Hamburg in 1943]. Of my father taking me back to school properly dressed and inspecting one of his camps en route. Left to amuse myself I fell in the stream near the entrance and of his efforts that ensued to make a very grubby boy presentable again. On another occasion, stopping at the well-known hotel at the entrance to the New Forest (Bear’s Cross) and eating perhaps the most disgusting meal ever; badly cooked cod and boiled cabbage. Even with rationing it was a disgrace. Which reminds me. After the war restaurants were not allowed to provide meals that cost more than 5/-. My mother took me to a café in Parkstone where we were served what purported to be chicken. I bet that’s rabbit she remarked. How times have changed. And talking of rations, the dried eggs, spam, margarine, my father preserving eggs in a bucket of some sort of brine and somehow wangling chocolate bars filled with a rather dubious iced sugary substance at the NAAFI for me to take back to school. These were doled out periodically from the tuck shop and kept in my locker where the mice made a mess of them with their droppings and wee. But that did not prevent me from eating them or swapping them for more desirable items, like the little toy mouse a boy had been given by a living in teacher, poor kind Miss Kirkpatrick. As her nickname demonstrates (Kirkpatrick> Gurckpotsick), we were still very much little kids in our early days, and toys, teddy-bears and the like were still part of our life and our humour commensurate.

My father was now based in an office at Westmoors and I remember his getting one of his draughtsmen to coach me in crossing the famous Pons Asinorum of proving the Isosceles Triangle problem (not just knowing the answer in those days, but being able to prove it, QED). For a while we lived in a bungalow nearby, where at the end of the lane was a Gypsy encampment (“Wanna a fight Mush?”). But for my mother and me, our peripatetic existence started again, when he decided that we would be better off down the way at “Burnbrae”, a hotel in Dudsbury (part of Ferndown) run by CS friends, the Tites, which we moved into in June 1943. It was then, like West Moors, a very rural setting with extensive grounds. Beyond the little stream at the bottom lay woods and fields (now part of some golf extravaganza) and it was while there that GHIS came to stay also and I became fully accepted. Two little memories remain firmly with me. The first was when I started chatting with an Italian Prisoner of War on day release working in the fields, and we ended up going for a long circular walk back to the hotel. Doubtless I reminded him of his own absent family and for a few moments help him forget present realities. But imagine today, the outcry and worry of a man taking a little boy off on his own all alone in the country! The second was the pineapple. The father of a Fan Court boy staying in the hotel during the holidays was in the RAF, based in the Gold Coast [Ghana], and came on a flying visit, presenting us with the real thing. It was not appreciated; we much preferred the sweet syrupy stuff that came in tins, preferably with concentrated milk. And one more memory when near the end of the European War my father (who had by now become involved with Mulberry Harbour) took me to Southampton docks to see the two Cunard Queens (The Queen Mary, three funnelled and the Queen Elizabeth [I] two funnelled), still in their battleship grey as troop carriers, moored alongside each other.

Post war pre-Harrow: Home and Fan Court 1945-7. Music was my passion and I had become a reasonably good pianist for my age, encouraged by my mother who was a qualified piano teacher. My strength was also my weakness, I was good at sight-reading which meant I tended to hack through things rather than working at them. After the war, the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra was resuscitated under the direction of a Jewish refugee, Rudolf Schwarz, whose concerts I regularly attended in the Pavilion. Records (78s) were primitive and costly so there were few opportunities (except for the BBC) to get to know even the standard repertoire. The thrill of hearing a well-known classic for the first time, live in the concert hall is something few know today. The same thing incidentally applies to works of art: reproductions are now two a penny and any Tom, Dick or Harry or their female equivalents, can learn to distinguish between a Rubens and a Tintoretto, or a Monet from a Manet. For most then it meant visiting museums or the odd postcard, for such art books as existed before modern mass production were for specialists and expensive. Perhaps that was why local initiatives were more frequently encountered. Ours was the Poole Music Club, run it was said by the Communists. Whatever, it produced some marvellous opportunities for recitals by big names from before the war. Elizabeth Schumann, like the Cortot recital in the Pavillion, are two that spring to mind. The Poole hall was of the simplest with the piano on a raised platform in front, and a cafeteria on the right. After the coffee break the main item of Louis Kentner’s recital was Beethoven Op 111. As he began that marvellous hushed beginning of the second movement, suddenly the café door was flung open and a waitress with a tray of plates, professionally held high on an upraised arm, marched obliviously in front of the stage, passing round to the kitchen side where a door was similarly unceremoniously flung open and the plates deposited con brio. Unperturbed, Kentner simply raised an eyebrow as the soft melodies continued to unfold. At another recital the pianist Pouishnoff announced that he would play as an encore a Czerny study that would be familiar to all budding pianists. I myself was working on it as too my sister Ruth who had decided that she would have another go at learning the piano. As we left she pronounced in a doctoral tone that she hoped I had observed how the piano should be played. “And did you recognize it?” I responded. She hadn’t!

Of Fan Court I have no specific memories in my last two years. Little changed as far as the boys were concerned. I was growing up and presumably working quite well in my usual cruising sort of manner, because I passed into Harrow with a high Common Entrance, though below scholarship standard (it was not until my last 18 months at Harrow that I really pulled my finger out and won an open scholarship to Oxford to TCE’s delight). I do remember however going to Wimbledon (1946?) and seeing the two Princesses: presumably someone had given the school tickets. Behind the scenes, the pre-war plan to expand was resuscitated, with the intention of building a house for the Headmaster which would free up space in the main building, the objective for economic viability being 85-90 pupils. But with rationing, shortages of materials etc as restraining as ever, if not more so, nothing could be done, although planning and financial appeals were pursued. In the meantime, fees were raised during my last year (and again the next). Just how small the school was during the time I had been there, is brought out in a speech by TCE celebrating its 21st birthday in 1953. The number of pupils it had educated was less than 250, 60 of whom were still at their public schools, where many were being very successful.

My last memory appropriately, is of the occasion when leavers were traditionally gathered together below the tulip tree for what was believed to be a talk of “the birds and the bees” variety. If it was, it was pretty discreet, the only thing I retain was the warning to avoid the attentions of older boys!”