Fan Court School

McGregor, Class of 1966

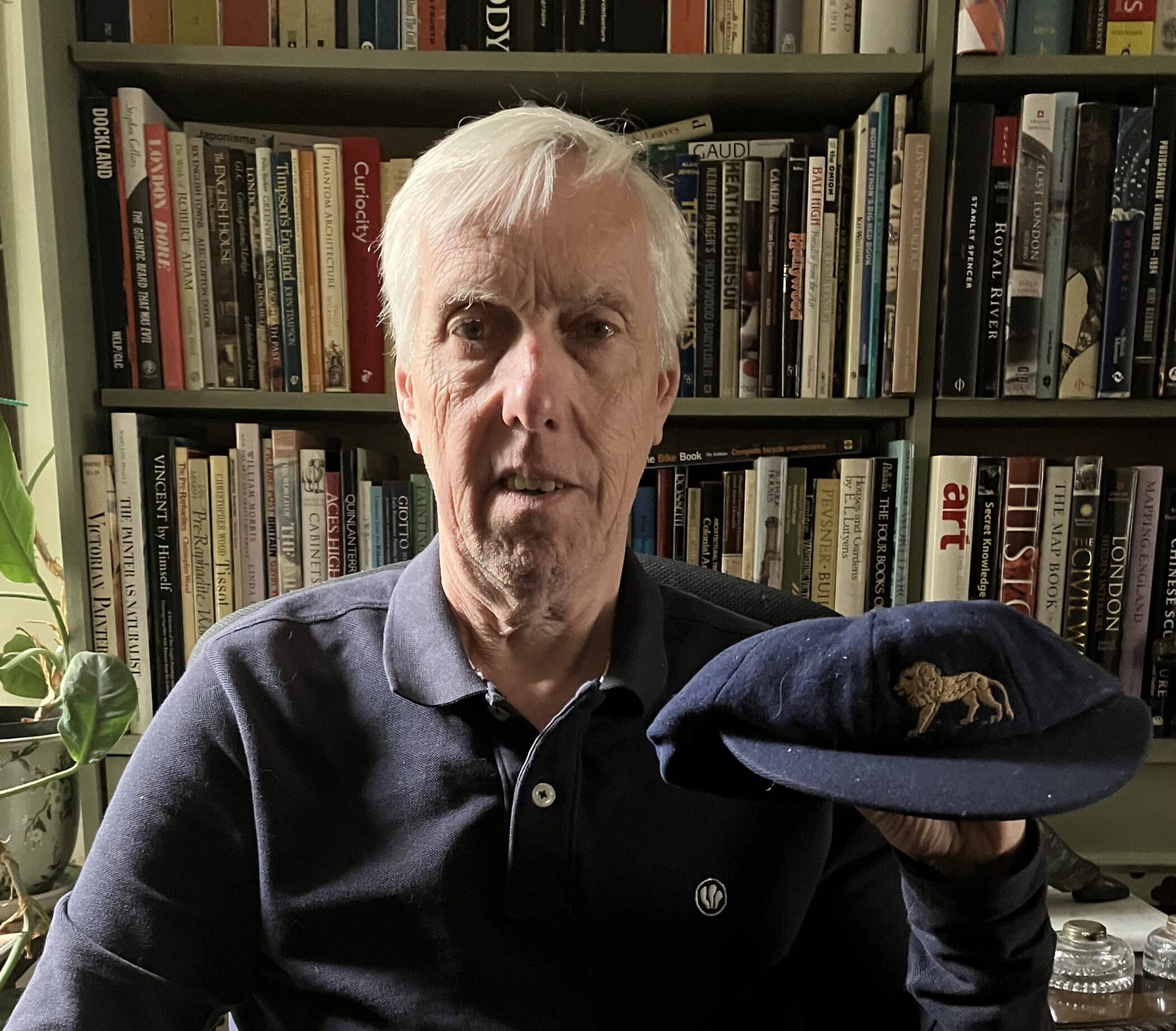

Neil Grey

Whilst his sibling Claire (Norwood, Class of 1967) attended Claremont School, Neil was a boarder at Fan Court School. Funny memories include a drama performance on Fan Court Day halted by thundering planes enroute to Heathrow, unpicking the sports team list scrambled into anagrams by a Master and the race for the comfortable leatherback chair in the library, the distinct smell of the cricket pavilion:

“Just getting to Claremont and Fan Court was a challenge for my sister Claire and me, as we lived in the northeast. The journey took all day by train including the perilous crossing of London on the underground. I was in McGregor House at Fan Court and arrived on my first day with a suitably tartan rug which even now continues to live out its threadbare dotage serving as ground cover for occasional picnics. It still bears the distinctive blue copperplate name tag with my school number, 16.

The most unexpected things stick in the memory from Fan Court; Mr Snape’s distinctive tread as he patrolled the landings after lights out; the resinous smell of the cricket pavilion (more a garden shed with ideas above its station), the French boy who described his toes as foot fingers; being shown a dead badger, killed on the road, and lying in state temporarily in the otherwise out of bounds apple house, unsafe because of its collapsing roof; a big crowd of us throwing sticks to dislodge conkers from the horse chestnut tree; being hit repeatedly on the head by many conkers and sticks falling from the same tree.

In class, arithmetic was taught using coloured Cuisenaire blocks, French through the technological miracle of the language laboratory, our English vocabulary was enlarged by learning new words every week. The class would spell out each letter in unison. A word would remain on the list until everyone in the class could spell it. No one wanted to be the one person who couldn’t. Today, and it only ever happens when I write the word ‘thorough’, the ghost voices of that same choir pop into my head and take me at a brisk canter through the complicated knot of vowels and consonants hidden in the word’s core.”

“We read for an hour every day after lunch; the fastest to reach the library from the dining room could claim the most comfortable chairs – we called them spring backs and leatherbacks – but this prize came with some jeopardy as the occupant could be turfed out by a senior boy who had that privilege. We spent hours covering all the library books with plastic from big rolls. I remember making covers for the three volumes of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings and finding it difficult to imagine that anyone would be able to read them all. Later on, I was obliged to spend this time in one of the dormitories learning the violin. It wasn’t a success; both of us came away from it a bit damaged.

Times were changing; boxing had been dropped before I arrived, but judo introduced while I was there. My certain pathway to mastering the martial arts stumbled at the first step as the forward roll proved beyond me. Alongside formal sports we played French cricket, tip and run, pirates (being chased around the gym equipment without touching the floor) and round-the-table-table tennis (minimum three players, but more fun with six). We played Owzthat, a tabletop cricket game that came in a little blue tin which contained two hexagonal metal rods that were rolled like dice. Teams were eclectic but scores were recorded meticulously. John Lennon and Alexander the Great might open the batting against the fearsome pace attack of Mahatma Gandhi and Florence Nightingale.

For afternoon games, teams were posted up beforehand. I wish I could remember who but one of the masters would write our names backwards, scrambled into anagrams or in the form of puns. The covered area outside the changing room where football and cricket boots were donned was called Edom after a verse from the Psalms, ‘Over Edom I will cast My shoe’. When we came in cold after the game, we would hug the huge hot water cylinder which served the showers to get warm.

Despite what is shown in the Fan Court film – in which I make a fleeting appearance – the main stairs were strictly reserved for senior boys and staff. When I finally reached that high office, I walked down them for the first time feeling like James Cagney in Yankee Doodle Dandy.

The broad roots of the Copper Beech tree at the edge of the lawn were used as a downhill racetrack. Model cars were released at the top to see whose could travel the furthest by gravity alone. Great care and attention were lavished on making sure the track was as smooth as possible. Mud embankments were added for faster cornering. We had crazes which came and went, phosphorus paint (certainly banned now on safety grounds), walking on stilts, mah-jong, collecting bubble gum cards – although bubble gum itself was not allowed. The Beatles were highly collectible but the series on the American Civil War was considered too bloodthirsty and not permitted.

Older boys were allowed to carry sheath knives – for bushcraft. Sunday afternoons were spent in the shrubbery lighting fires, building dens and trying to pull down young trees in the sport which we called bush crashing. Our favourite thing was tossing fragments of asbestos cement into the fire because they would detonate with a satisfying loud crack and send out lethal fragments in all directions. No health and safety in those days. We made ‘cigarettes’ from dried leaves and newspaper. No one got further than an attempted first puff owing to their tendency to ignite the eyebrows. Which is probably just as well.

The most common punishment for misdemeanours were ‘rounds’. These were circuits of the perimeter of the main lawn to be taken at a run. The number of rounds denoted the seriousness of the infraction. Naturally we looked for shortcuts or took breathers where the view from the main building was obscured by rhododendrons or the huge Wellingtonia tree with its wonderfully spongy bark. In the centre of the first floor landing was a raised sarcophagus-shaped structure which allowed heat and ventilation to pass between the two floors. This had a polished wooden top and a mythical status. It was widely believed that those guilty of the worst crimes would be made to sleep on this hard wooden surface as a punishment. There was of course absolutely no truth in this at all.

There were rewards too. ‘Copies’ and ‘half copies’, awarded for good schoolwork, both carefully recorded in a book, each initialled by the form master. Poems of sufficient merit were transcribed into a special book.

I can trace my lifelong love of reading and books to the Summer evenings after we had gone to bed but were permitted to read whilst there was still daylight outside. My battered paperback copy of Alan Garner’s Weirdstone of Brisingamen still bears Mr Andrae’s initials to signify it was approved reading material. Beds had to be made with perfect hospital corners and were subject to rigorous inspection. If they were found wanting, they were pulled apart and the hapless bed maker had to start again.

On Fan Court Day a huge marquee would be erected. When we performed outdoors someone with a whistle would halt the performance on the approach of an aeroplane heading to Heathrow. Once it had passed the whistle signalled again and the performance resumed. It didn’t do much for dramatic tension. I appeared wearing Miss Ward’s oriental pattern pyjamas, a coolie hat and a pan stick moustache as a Chinese man. I read a Bible verse as part of a performance about William Tyndale’s translation of the Bible into English .

We had model boats powered by clockwork which we sailed on the swimming pool. Keen swimmers would pretend they couldn’t swim to obtain an extra hour in the pool being ‘taught’ before it was opened to all comers. No one seemed to notice these hapless splashers immediately shooting into the distance powered by an effortless front crawl on the turn of the hour.

I had £1 pocket money each term of which 4d a week had to be withdrawn for the church collection. I can still feel the weight of those four big coins inside my woollen glove .

At Fan Court, because many families were local or boarded weekly, boys went home for the weekend, or their parents travelled down to take them out. That wasn’t possible for me being so far from home. At some points there could be very few of us left in school. One weekend there were only two of us. Mr Tucker took us swimming at Frensham Ponds and bought us chips and baked beans in a transport café on the way back. I didn’t believe food as wonderful as this existed in the world.”

“In the groundsman’s hut amongst a stand of trees which contained our favourite horse chestnut, someone found a discarded gentlemen’s magazine. Mild to the point of anaemia compared with today’s equivalent it did however contain some coy images of nude women. Airbrushed so comprehensively that without close examination they might as easily have been pictures of dolphins, the groundsman had traced their outlines with a biro, presumably to perfect his skill at drawing freehand curves and circles. To us this abandoned piece of ephemera took on all the mystical significance of the Dead Sea Scrolls; it was spoken of in hushed tones, made accessible only to those prepared to be bound perpetually by blood curdling oaths of secrecy and handled with the reverence of an ancient artefact. Not all of our education at Fan Court came from the curriculum.

The gong which summoned everyone at meal times was at the bottom of the main staircase. Senior boys would be responsible sounding it. This was no simple task, it required technique. Not for us the two or three ponderous strikes which preceded films from the Rank Organisation. For a start there was the implement; the gong was struck with the wooden handle from a claw hammer. It had a hole at one end through which a loop of string was used to hang it from the gong when not in use. It was inscribed ‘Hickory’, presumably the type of wood or perhaps the manufacturer. When mealtime time arrived, indicated by the gold sunburst clock at the top of the main stair, the performance could begin. Starting at the outer edge of the gong a very light but rapid tapping would be the barely audible overture. The intensity was increased gradually, and the point of impact moved inexorably towards the centre of the gong as the volume increased. The trick was to keep the gong ringing but minimise the amount it swung. The composer of this complex work has been lost in the mists of time.

We assembled first, had our hands inspected for cleanliness (both sides), then filed into the dining room. We sat eight to a table times, three either side, one at the bottom and a member of staff at the head. They moved between tables, and we rotated around our table. This created a deadly game of Russian roulette, as no one wanted to be at the top when it was the headmaster’s turn with us. As delightful as he was, it is part of a headmaster’s job to be truly terrifying. Each table would be given a rectangle of butter to be shared. Someone was elected to score the top with a knife, dividing it into the right number of equal portions; vertical cutting when you took your share was scrutinised fiercely.

If you didn’t like the look of the food, you could ask for a smaller portion. This was signalled by resting your fist on the table edge with the forefinger pointing upward at an angle, as if you were discreetly drawing your hostess’s attention to some cobwebs the domestic staff had missed without alerting the other guests.

Sometimes even a smaller portion proved too much for me. As plates had to be empty before they were removed, I developed a miniature dry stone walling technique, piling up uneaten food into a narrow vertical structure across the middle of the plate on top of which I could balance my knife and fork. From above, the theory went, the plate should look empty. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t.

No such problem if you were ill, or ‘upstairs’ as it was called. Left alone with your lunch, it was a simple matter to grab a handful of cabbage, evidently made from the recycled celluloid collars of Victorian bank clerks, and pop next door to the bathroom where a simple flush would, as it were, cut out the middleman.

The passage of time has diminished the enormous impact that pop music had on our developing minds. Here was something visceral and exciting made expressly for us, not mediated by teachers or shaped by adult values. On the same radio which had brought us the tragic news of Kennedy’s assassination in Dallas, we listened each week to the top 20 countdown on Pick of the Pops, entranced by Alan Freeman’s hundred miles an hour delivery. But that was only the half of it. Older boys had access to the Forum, a kind of club room which we used for leisure activities. Here there was a record player. Singles cost 6/8d (so, three for £1), and came from Woolworths. In an era incredibly rich in musical innovation that would set the foundation of a whole new youth culture, we first heard the prolific output of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. Imagine hearing those amazing songs for the very first time. One of our favourites records was ‘Keep on Running’ by the Spencer Davis Group. This would be mimed expressively with snooker cues as guitars and music stands as microphones. Someone would be tasked to stand by the light switch and turn it on and off rapidly for the full psychedelic experience.

Of midnight feasts I can remember only one, for reasons that will become apparent. At that time, I was in a smaller dormitory along a passage and down a short flight of stairs from the main first floor. It was probably a part of the house originally designed for the domestic staff. The teacher on duty after lights out had already picked up the giveaway sounds of something illicit going on. Suppressed giggling, the squeak and hiss of Tizer bottles being opened, and the teeth-threatening crunch of sherbet lemons. Planning to creep up on us, the first we knew of his presence was a tremendous crash as he hit the floor horizontally outside the door having miscounted in the dark and missed the bottom step. The shock inside the room resulted in a shower of liquorice Allsorts which rained down on the innocent and guilty alike. Luckily, he wasn’t hurt but the subsequent interrogation had already been fatally undermined by the damage to his authority. Those of us who were not pretending to be asleep were busy stuffing hankies in our mouths to stop laughing. Someone even asked him what he was thinking of waking us up like this. I wish it had been me.”